Minimum unit pricing

The Sheffield Addictions Research Group has been highly influential in the introduction of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol in Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland. Here we answer some common questions about minimum unit pricing.

What is minimum unit pricing?

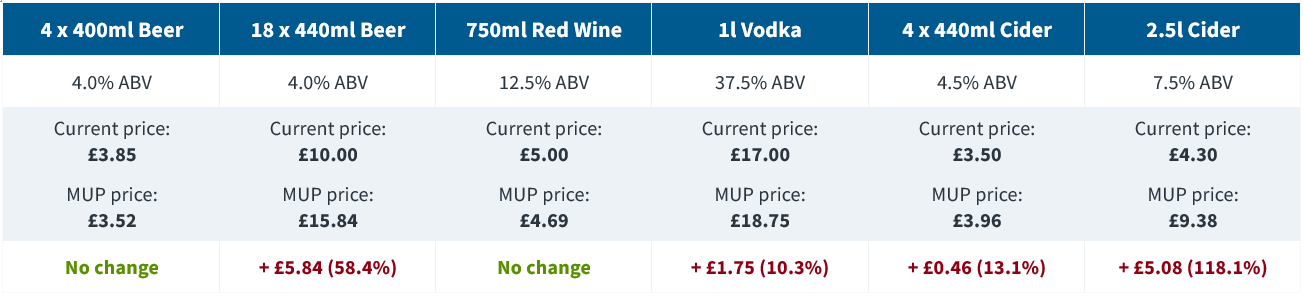

A minimum unit price (MUP) sets a floor price below which a unit of alcohol cannot be sold to consumers. This means that the floor price is directly linked to the amount of alcohol contained in the product. For example, a 50p MUP would mean that a pint of beer containing two units of alcohol would need to cost at least £1.00 and a bottle of wine containing nine units would need to cost at least £4.50. The table below shows the effect of a 50p MUP on a range of alcohol types.

MUP only directly affects products sold below the floor price. This means the price of a pint in the pub would not be affected, nor would most other drinks sold in pubs, restaurants or nightclubs. All of these are already priced at well above 50p per unit. Instead, the main impact of MUP would be on alcohol sold in supermarkets and off-licences, particularly multipacks of beer and cider, cheaper spirits brands and strong 'white' ciders.

Where does the additional revenue from the minimum unit price go?

Introducing an MUP leads to an increase in the sales price of some alcoholic products (i.e. those that were being sold below the MUP threshold). Although people will respond to these increases by buying less alcohol overall, our total spending on alcohol is likely to increase.

An important difference between an MUP and an increase in alcohol taxes is where this additional revenue goes. When taxes increase, the additional revenue goes directly to government. Under an MUP, although a proportion of the increase in sales price for affected products does go to the government in the form of VAT, the majority of the additional revenue from selling alcohol at higher prices goes to the retailers and producers of alcohol. As a result, we would expect the profits of shops, supermarkets and companies who make alcoholic products to increase under an MUP.

Some commentators have proposed the introduction of a 'windfall tax' on the profits of alcohol retailers and producers to recover some of this additional revenue for government. However, to date, no country with an MUP has introduced such a measure.

Which countries have introduced minimum unit pricing?

Scotland passed legislation to introduce MUP in 2012 and implemented a 50p MUP in May 2018 after a five-year legal challenge led by the Scotch Whisky Association. In August 2024 the Scottish government increased the MUP level to 65p per unit.

Wales introduced a 50p MUP in March 2020 and the Republic of Ireland implemented an MUP set at €1 per Irish standard drink (equivalent to around 70p per UK unit) in January 2022. The Northern Irish government have also announced their intention to introduce an MUP.

Beyond the UK and Ireland, Armenia and Australia's Northern Territory also have MUPs that apply to all alcohol, while Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Slovakia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, several Canadian provinces and Australia's Northern Territory all have forms of minimum pricing in place that cover at least some alcoholic products (e.g. a minimum sales price for a 700ml bottle of vodka).

What is the evidence for minimum unit pricing?

There is a strong, and growing, body of research evidence showing that MUP policies are effective at reducing alcohol consumption and associated harms. This evidence falls broadly into three categories:

Across all three forms of evidence, and many individual studies, a clear picture has emerged showing that MUP is effective at reducing alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms.

How does minimum unit pricing affect particular groups?

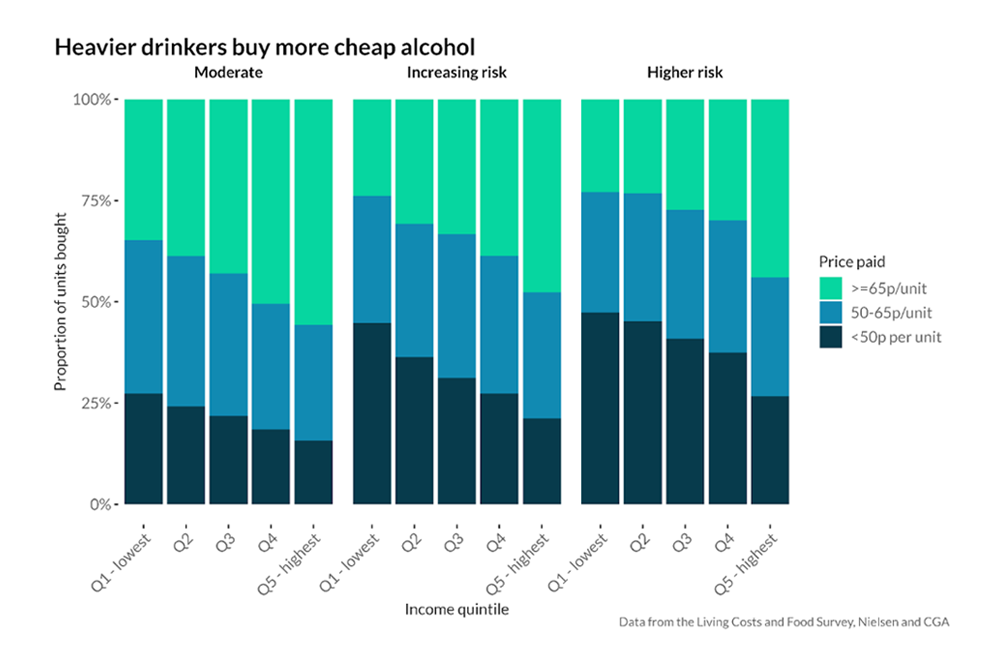

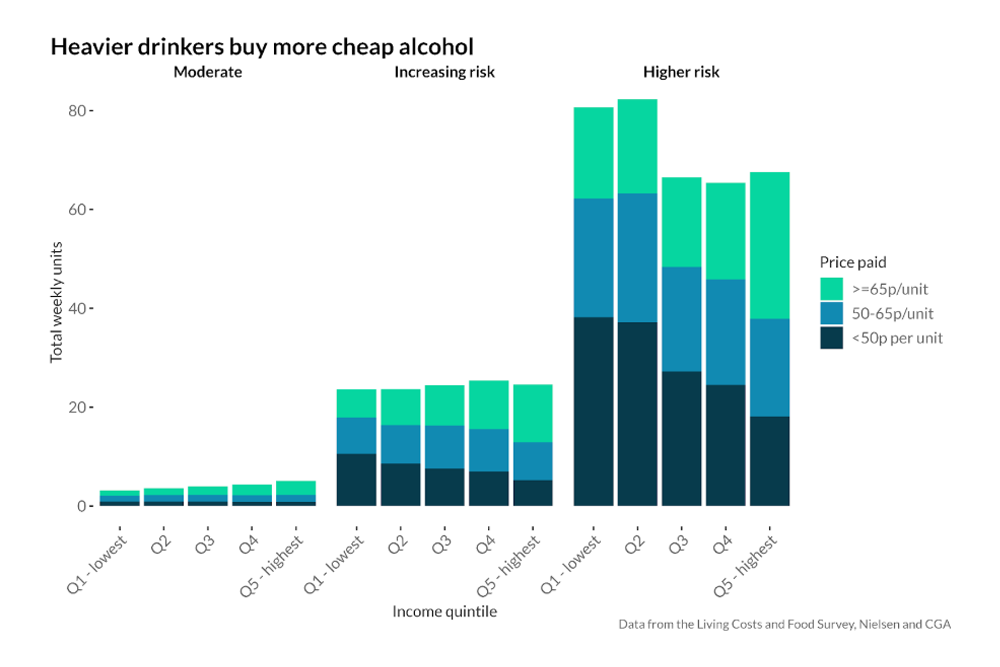

A key part of the appeal of MUP to policy makers is the fact that it effectively targets the cheap alcohol, that is drunk disproportionately by heavier drinkers, while having relatively little impact on the alcohol consumed by moderate drinkers. This remains true even among lower income groups, who pay less, on average, per unit of alcohol, than those in higher income groups.

Figure 1 shows how the proportion of alcohol bought in different price bands differs between drinker groups and income quintiles. This illustrates that while drinkers on lower incomes buy more cheap alcohol across all levels of drinking, heavier drinkers buy a substantially greater proportion of their alcohol at the lowest prices within each income quintile.

The targeted impact of MUP becomes even clearer when we convert these proportions into total units purchased each week, shown in Figure 2. Here we can see that the overwhelming majority of alcohol being bought at the lowest prices is being purchased by heavier drinkers, particularly heavier drinkers on lower incomes.

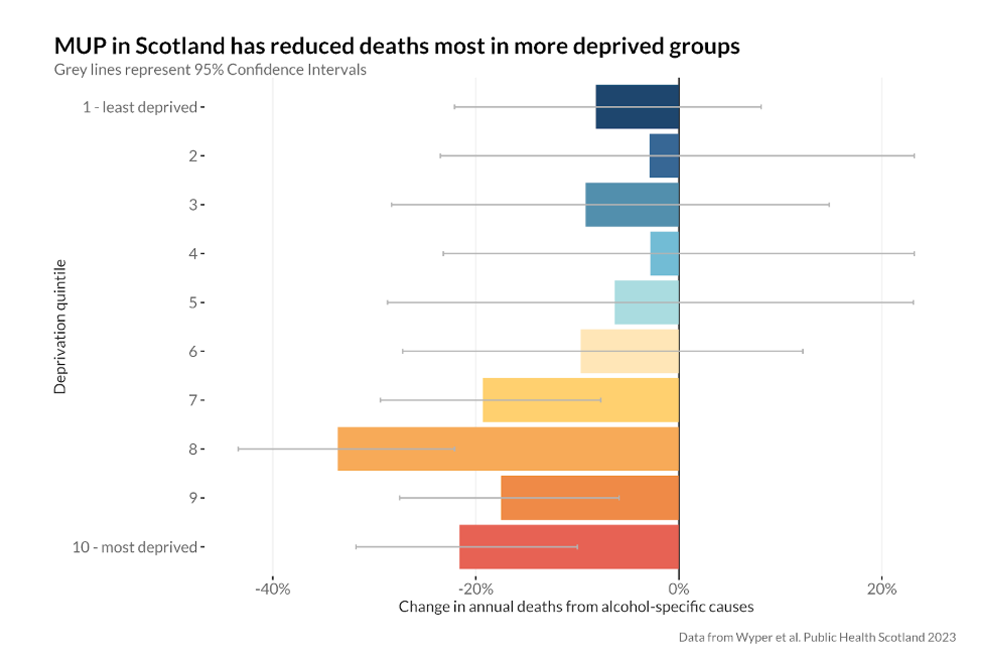

Having a greater impact on the price of alcohol purchased by heavier drinkers on lower incomes is important for the inequality impacts of MUP. Alcohol harm rates are substantially higher in more deprived groups, with around four times as many deaths from alcohol-specific causes in the most deprived, compared to the least deprived, 20% of the population. As a result, reducing alcohol consumption among heavier drinkers in more deprived groups is key if we want to reduce alcohol-related inequalities in health.

Findings from the evaluation of the introduction of MUP in Scotland have demonstrated this effect in practice, with the largest reductions in deaths from alcohol-specific causes being seen in the most deprived groups. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Why introduce minimum unit pricing rather than alcohol duty increases?

MUP

- Only increases the price of the cheapest alcohol

- More effectively targeted at heavier drinkers

- Bigger reduction in health inequalities

- Price increases must happen

Tax

- Increases the price of all alcohol

- Additional revenue goes to the government through tax increases

- Still reduces alcohol-related harm and health inequalities, but to a smaller degree

Increasing alcohol taxes is another effective way of reducing alcohol consumption and related harm. However, MUP specifically targets the cheaper and higher-strength alcohol that is favoured by heavier drinkers. As a result, it leads to larger reductions in consumption among high risk drinkers and larger reductions in deaths and hospital admissions caused by alcohol.

Our previous analysis has found that, to achieve the same impact as a 50p MUP, alcohol taxes would need to increase by between 27% and 70% depending on which outcome you wish to match.

Other considerations when comparing the two policy options include that the additional revenue from higher prices goes to retailers under MUP but to Government under increased taxes. MUP also legally enforces price increases for products being sold below the MUP threshold, whereas the cost of tax increases can be either absorbed by the industry, distributed unevenly across alcoholic products or passed on to non-alcoholic products.

In line with these possibilities, our analyses suggest that when alcohol taxes go up, cheaper drinks increase in price by slightly less than would be expected and the price of more expensive drinkers increases by slightly more than would be expected. Essentially this means that people buying more expensive alcohol are subsidising lower price increases for the cheapest products.

It's also important to recognise that MUP does not have to be treated as an alternative to increasing alcohol taxes as both policies can be enacted together.

Talk to our experts

To discuss our work on minimum unit pricing for alcohol drop us a line at sarg@sheffield.ac.uk and we'll get back to you as soon as we can.

Research on minimum unit pricing

-

New report on minimum unit pricing for alcohol in Wales

The Sheffield Addictions Research Group (SARG) has published a major new report that models the impact of alcohol pricing policies on alcohol consumption and harm in Wales.

-

SARG experts to present at IAS webinar on minimum unit pricing

SARG Director Professor John Holmes and Research Fellow Dr Abi Stevely will be sharing their extensive knowledge and insights on minimum unit pricing (MUP) at a webinar hosted by the Institute of Alcohol Studies (IAS).

-

New modelling of alcohol harms in Scotland

The Sheffield Alcohol Research Group has today (20 September 2023) published a major new report on the impact of alcohol pricing policies, alcohol consumption and harm in Scotland.

-

Evaluating the impact of minimum unit pricing in Scotland on harmful drinkers

This project evaluated the impact of Scotland's minimum unit pricing (MUP) policy on people drinking at harmful levels, including those with alcohol dependence.

-

Does minimum pricing reduce the burden of disease and injury attributable to alcohol in Canada?

This research used the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model to estimate the potential effects of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol on consumption, spending, and alcohol-related harm in Wales, including health, crime, and absenteeism.

-

Modelling the impact of minimum unit pricing for alcohol in Scotland

Since 2009 the Sheffield Addictions Research Group has undertaken a number of modelling projects for the Scottish Government to appraise the impact of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol.

-

Modelling the impact of minimum unit pricing for alcohol in Wales

This research used the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model to estimate the potential effects of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol on consumption, spending, and alcohol-related harm in Wales, including health, crime, and absenteeism.

-

Appraising the effect of implementing local minimum unit pricing on alcohol consumption and health in the North West of England

This project aimed to provide evidence about what would happen if minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol was introduced by local authorities in North West England.