Smoking rates have declined over time, yet tobacco use still remains one of the largest preventable causes of illness and death worldwide. In England alone, about 5.3 million people currently smoke tobacco – that's nearly 13% of all adults.

You're probably familiar with the idea that people who smoke are more likely to reach for a cigarette when they feel stressed or down. Some scientific research backs this up, suggesting that a bad mood can make tobacco more appealing.

But what is really going on in our brains when our mood sways the decisions we make based on how rewarding or desirable something feels? Our recent study directly addressed this question by using computer modelling to examine how mood influences the brain's decision-making processes.

Using computer modelling to understand decision-making

My research uses a technique called 'drift-diffusion modelling' to understand how people make value-based decisions. Simply put, this model explains decision-making as a process where people gradually collect 'evidence' for one option over another.

For instance, imagine you're choosing a snack in a convenience store. You might think about how tasty each one is, its cost, calorie content and how easy it is to eat on the go. Your brain weighs up these little bits of information (the 'evidence') until one snack seems like the best choice based on what you value most at that moment. And that's the one you decide to buy. This same gradual process of weighing evidence is what we believe happens when people make decisions about smoking.

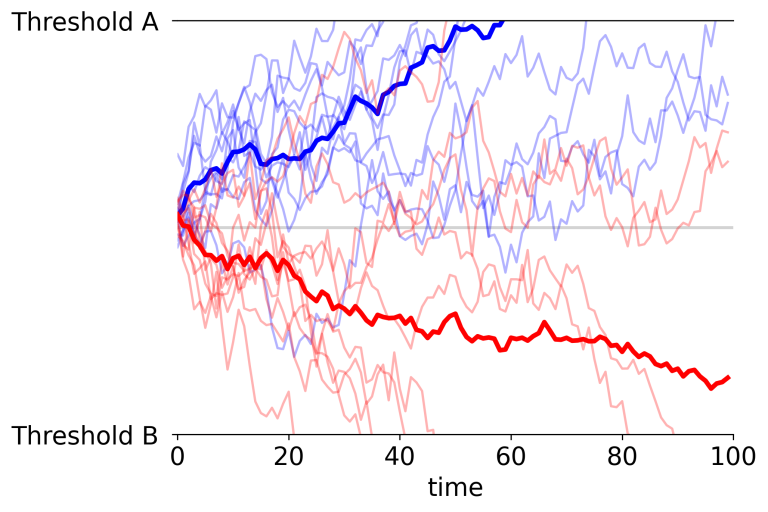

The graph below shows how this process looks in our computer model. The coloured lines represent the way our brains collect evidence over time (blue lines for Option A and red lines for Option B). The wobbles indicate the natural uncertainty in our thinking as we weigh the pros and cons of each option. Once the evidence for an option becomes strong enough, it hits the threshold, and a choice is made – in this case, Option A wins.

Graphic depiction of the drift-diffusion model for choosing between hypothetical options A and B.

But how does this all relate to mood and smoking choices?

We worked with colleagues at the University of Washington to design a study which combined drift-diffusion modelling with mood induction – that is deliberately trying to make people feel a certain way – to examine how mood affects the choices of people who smoke every day.

Our study: putting good and bad moods to the test

We used an online platform to recruit 49 people who smoke at least ten cigarettes a day and had been daily smokers for over a year. Across two separate testing sessions, we primed them to experience either negative or positive mood, before asking them to complete a task designed to measure their value-based decision-making about various things, including tobacco and other unrelated items.

How we manipulated moods

In line with previous research on mood induction we used carefully selected videos and statements. To induce a negative mood, participants watched the heartbreaking scene from The Lion King – yes, the one where Simba tries desperately to wake his dad, Mufasa. This was followed by mood-lowering statements like "When I speak, nobody really listens".

On the other hand, to induce a positive mood we went with something more upbeat: the Hakuna Matata scene with Timon and Pumbaa (it means no worries!), paired with affirming statements like "Most people like me".

The decision-making task

Once a participant's mood had been primed, we asked them to complete a simple image rating exercise. The participant looked at a set of pictures – some related to tobacco and others unrelated – and rated how much they liked each one.

Then, in the next part of the task, participants were shown pairs of images from the same category (e.g. two tobacco images or two non-tobacco images) and asked to choose between them.

During this process, we measured their reaction time (how quickly they made decisions) and accuracy (whether they consistently selected the images they previously rated higher). These measurements were used in our computer modelling to analyse the links between mood and decision-making.

What the study found

As expected, after participants watched videos designed to induce a negative mood, they reported decreased happiness, increased sadness, and a stronger craving to smoke compared to when they watched the videos designed to make them feel positive.

However, what we found when we looked at their actual decision-making was less straightforward, and the results of our computer modelling were quite surprising.

When we explored participants' decision-making data (how fast and accurate they were) with computer modelling, we found that their mood – whether good or bad – didn't actually change how much they valued tobacco or the tobacco-unrelated alternatives. This finding goes against what some previous research has suggested.

What this means

These findings are important: they suggest that the common idea that people smoke to make themselves feel better when they're down might not be the whole story. It's possible that the relationship between our mood and how much we want things like cigarettes is more complex than we currently understand.

This idea is supported by a large study that looked at daily survey data from over 12,000 people. They found that people were more likely to drink, and to drink heavily, on days where their mood was positive. Although specific to alcohol, these findings also challenge the common assumption that people drink primarily to cope with negative moods.

More broadly, these findings contribute to our understanding of addictive behaviours. If the link between negative mood and substance use isn't as straightforward as often assumed, this has implications for how we approach addiction treatment and prevention.

A couple of caveats

There are a few important limitations to note.

Given that the study was conducted online, we lacked direct control over participants' environments, so we couldn't account for how comfortable or focused they were while taking the test for example. Furthermore, we didn't explore all the potential reasons why someone might smoke, such as whether they typically use smoking to manage or cope with stress.

Additionally, since we didn't include a neutral mood condition, our comparison is limited to negative and positive moods, rather than examining how these moods influence decision-making in comparison to a neutral state.

These are important avenues that we are keen to explore in future research.

This blog post was based on the following paper:

Copeland A, Dora J, King KM, Stafford T, Field M (2025) Value-based decision-making in daily tobacco smokers following experimental manipulation of mood Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000781

This research was approved by the University of Sheffield ethics committee. All participants were screened to ensure the mood induction would not cause distress, in addition to completing a mood repair exercise before finishing the study.

The author would like to thank Anne Greaves for her contribution to this post.